This article is adapted from Bob Adams' play Place of Angels. It is slated for publication in

Vietnam magazine in 2006.

Healing Wounds

by Bob Adams (2nd Batt. 1st Mar. 68-69)

with Will Kern

God and all of North Vietnam could see us.

We were outside Khe Sanh on Operation

Scotland II and had stopped at midday to take

a bit of rest and to eat. We had set up on the

side of a hill, far too exposed for safety. We

were all very tired from humping the hills on

this operation. 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines.

You’d think we’d be smarter. It was a careless

thing to do.

As we got up to move, the NVA started walking

mortars in on us. The chaos is unimaginable.

The THUMP! of the mortars being dropped in

the tubes, and ejected. Then the explosions:

BOOM!… BOOM!… BOOM!… BOOM!… BOOM!

BOOM! BOOM! Sand and shrapnel

flying everywhere. Men separating and diving

in all directions. Shrieks of “INCOMING! ...

INCOMING!” The ground shaking from the

detonations. Men lying still and eating the

earth to stay low. I found what seemed like a

small indentation in the ground and got down.

Then I heard the screaming. My best friend,

LCpl Jim Tucker, had been hit.

The date was May 11, 1968. I was a corpsman

in the US Navy but had been assigned to the

Marines. I joined the Navy in 1966 because I

thought it was a way of getting out of combat. I

was absolutely terrified of going to war.

In boot camp, I was given a choice of jobs and I

chose hospital corpsman because I had an

uncle who was a corpsman in World War II. He

served aboard an aircraft carrier, came home

and became a successful optometrist.

I saw something like that happening for me.

I picked corpsman without asking anyone who

might know what the job would involve. The

night I got back to the barracks and told my

CC, SMC Edward Chambliss, what I did he flew

into a rage. Imagine my surprise when I found

out that the thing I was most afraid of in the

world was exactly the thing I was going to have

to do. I was not going to be aboard ship. I was

going to be in a Marine combat unit. He was

so mad he told me he wasn’t going to wait for

the Cong to kill me. He was going to do it

himself.

I didn’t really belong in the military. I’m blind in

my left eye from birth, 20/400 and not

correctable. When I went for the eye test on

my induction physical, I couldn’t read the

chart. But I’ve been taking eye tests since I

was three and I know that the big letter is an

“E,” so I said to the doctor, “I think I can make

out an ‘E.’ ”

Slam, bang, bam, I’m a member of the United

States Naval Service. That was the state of

the military in 1966. They needed bodies so

badly they were taking one-eyed goofs from

Chicago who happened to weigh 100 pounds.

Even the recruiter said he never thought I

would make it.

Two years later, in Con Thien, I started my

tour. And got the word. As far as these

Marines were concerned there were two kinds

of corpsmen. One was like Doc Waller, a.k.a.

The Goat. He traveled with the command

group and didn’t like to live like a troopie. He

played it by the book, was a stickler for

protocol. If he found out you didn’t take your

malaria pill he might just as soon write you up

as talk to you about it. And he INSISTED that,

in any casualty situation, the wounded be

brought back to him. A BOOK thing. The

RIGHT thing.

Then there was Kid Squid*. (All of us Navy

were referred to as Squid. But if you were

liked and admired, they’d add a nickname).

Kid Squid lived with a squad, stood radio watch

like any other troopie, helped out in any way

he was needed. And Kid Squid’s deal was,

“Wherever you are – if you’re hurt, don’t worry,

I’m coming for you.”

What kind of corpsman was I going to be?

They would be watching. So I got it early. I

understood. Whatever the book said,

whatever technique I had been taught at Field

Medical School was out the window. No one

expected any less of you than that you join the

war with them, that you did for them what they

would do for you. You stood radio watch. You

carried your equipment and, if need be, theirs.

If it came to it, you put the medical equipment

down and picked up a weapon and fought for

them as well. And you NEVER waited in a hole

for some wounded Marine to be dragged back

to you. You came for them as they would for

you. And that was the word.

I was made to understand quickly that out

there, to those young Marines, the book meant

nothing. They had respect, admiration, and

affection for the Kid. He was one of them. And

he came for them. NO MATTER WHAT! The

Goat they didn’t have much use for. He knew

it, I think. And they knew it.

My best friend in squad was Tucker. A big

strong kid from New England, a great spirit.

We became good buddies, kind of a Mutt and

Jeff team. We looked out for each other, often

traveling close to each other on patrol and

sharing C ration meals together. By Khe

Sanh, I had been eating out of C ration cans

for three months. I could barely eat any of it

anymore. Tuck would make sure I got

whatever of his I could eat, as he could eat just

about anything.

Tucker and a couple of other guys committed

an act of larceny on my behalf. A shipment of

SP packs came into the CP, and Corporal Mick

Zullo, a Californian, went to ask the supply

clerk, Lt. Ken Daniels, for some cigars that

were in the packs. He did this because I was

flat out, and didn’t smoke cigarettes like

everybody else. Daniels told him to fuck off.

Zullo came back to our bunker and told

Tucker, and he was pissed. He wanted to go

back down to CP to argue the LT out of the

cigars, but he got talked out of it. Later,

Tucker, Zullo, and Pfc Charles Perry went to

an abandoned Army supply dump to scavenge

for food, or anything else we might need.

While there they found three SP packs that

had been left behind. Tucker said, “Fuck, let’s

get the cigars out of the SP packs for the

Doc.” The three of them carried the SP packs

back to our bunker, split them open, and gave

me the cigars, thirty in all. We took whatever

else we wanted and the four of us spend the

night burying the remaining supplies. They

could have been reprimanded for the theft, but

they were willing to take the risk. For me.

I had gotten so close to my squad by the time

we got to Khe Sanh. It was like we knew what

everyone was thinking and feeling. I felt a little

foolish with how much I had grown to love

these guys.

And there they were, dying on a hillside in

Vietnam.

We were not dug in and the shit was flying

everywhere. I heard someone yelling

“Corpsman! ... Corpsman! ... Doc! ...”.

I did not want to move. I never wanted to move

less than at that moment. The thought

occurred to stay put. After all. The mortars

are still coming. I could stay here and ...

And this is when, I suppose, the military

training I received kicked in. I flashed on my

old CC and “80 sailors to the fleet” and all this

is happening in an instant. Up I go moving to

my right, past a tree and to a gully where the

screaming is coming from. I see a couple of

my squad, and one of them is Tucker. He’d

been hit and was calling to me. The gully was

too steep and I was frantic to find a way down

to my friend. The fucking mortars are still

coming and I’m back and forth on that ridge

looking for a way down, running around like a

shithouse rat. Finally I see a way and down I

go.

He was hit in the back, neck, arms, and legs

with shrapnel that had ripped away at his flak

jacket. His face was cut and black from dirt

from his fall. He was screaming, “DOC ... DOC

PLEASE ... THE PAIN ... IT HURTS ... OH,

JESUS ... JESUS GOD ... DOC ... ARE MY

LEGS HIT ... JESUS DOC, THE PAIN ... HELP

ME ... HELP ME PLEASE ... JESUS GOD HELP

ME....”

Mortars started coming in close to where we

were. I was working on him, but he was too big

to move and everyone else was taking care of

someone. I didn’t know what else to do. He

was my friend and he was completely helpless

and he was screaming in pain and to keep him

from getting hit again I did what I know he

would have done for me: I straddled him to

shield his body from the incoming shrapnel.

He was still screaming and I told him it would

be okay and to try and stay still.

The next thing I know the mortars stop and

Tucker is screaming in pain. I made the

decision at that moment that haunted me for

many years. I gave him a shot of morphine,

not knowing enough about his wounds to know

if that was contra-indicated. What if, in all the

fear and madness, I missed a sucking chest

wound, a no-no for morphine. He could have

dyspnea, a severe shortness of breath that

would make breathing difficult if not

impossible. His heart could stop.

I lived with guilt for years every time I thought

about that day. Did I do enough medically to

treat his wounds? For all I knew, the morphine

made it a lot harder for him to heal and it could

have and seriously complicated his recovery.

Eventually Capt Clyde Woods and the

radioman and I carried his gear and Tucker

halfway up the hill to the Med Evac Landing

Zone. We loaded Tuck and the other

wounded and dead on the Med Evac

choppers. The choppers got in and out

quickly, as Luke the Gook and his mortar

tubes were still in the area. The jets had

preceded the choppers, so the NVA had

disappeared and the Med Evac went off okay.

I watched until Tucker’s chopper flew out of

sight. I wanted him to be safe and was freakin’

because I didn’t know if he would be. A little

while before we were sharing food on the side

of a hill and just like that, he was gone.

I didn’t know if I would ever see Tuck again but

I did know he made it home alive. My buddy

LCpl Dick Slade went home for a thirty-day

leave and came back to say he’d seen Tucker

at the Naval hospital in New England. He

looked away when Slade mentioned me. What

did that mean? I didn’t know, but I knew it wasn’

t good.

I tried contacting Tucker for three decades

after that. I felt extremely guilty. See, for me,

none of it was about God, Country, the Marine

Corps, my family, or any of that. It was about

my guys. They were mine and I was theirs and

I did what I had to do for that reason. I felt like

I had failed him. What if I didn’t do enough

medically to treat his wounds?

I finally got in touch. He was living on a farm in

Vermont. I called him, and I wasn’t sure if he

was going to hang up on me. I was relieved he

didn’t. We talked for a long time. He was glad

I called, it turns out. He always wondered what

had happened to me.

Finally I said, “I thought you were mad at me.”

Tucker didn’t know why I would think that. I

said, “You looked away when Slade mentioned

my name.” Tucker laughed. “Did Slade come

to see me? I don’t even remember. Jesus,

Doc, part of my elbow was blown away, and

half my hip. You couldn’t have done much

damage,” he said. “Slade.

I’ll kill him.”

These last three words were like beautiful

music to me. Just like that, a lifetime of guilt

was erased.

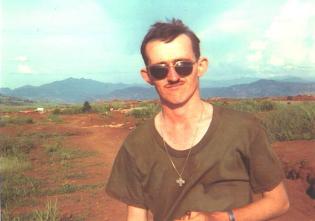

Bob Adams in Khe Sahn. April, 1968.

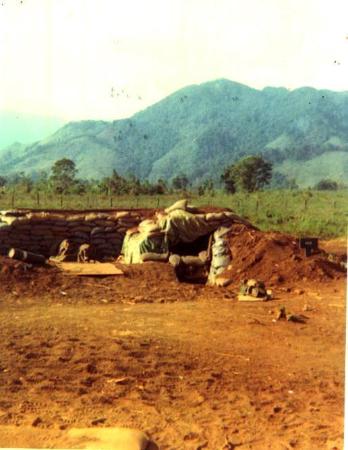

During Operation Scotland II. May, 1968.

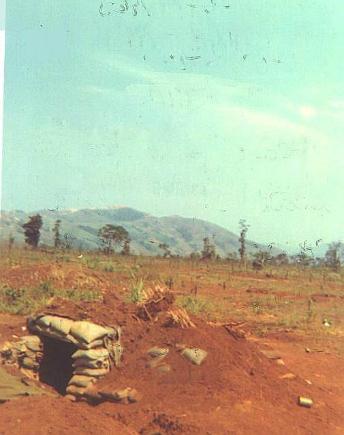

June 1968.

Khe Sahn, May, 1968. From left to right: LCpl Jim Tucker,

Pfc Charles Perry, LCpl Dick Slade, and Cpl Mick Zullo,

Bunkers at Khe Sahn (above and below).

Bob Adams was a Navy Hospital Corpsman serving

with the 2nd Battalion First Marines in Vietnam from

Feb 1968 to Feb 1969. Bob now works as a

Licensed Clinical Social Worker in the Chicago area

in private practice. He is a member of the 2nd

Battalion First Marine Association, a fellowship

dedicated to continuing friendships formed in combat

and caring for those still struggling with the

aftereffects of Vietnam. He is the author of Place of

Angels, a stage play recounting his tour of duty,

which premiered at A Red Orchid Theatre in Chicago

in 2000. He is married and the stepfather of three.

|